The Value in Visiting Cemeteries

Photo by Danni Matter

My fascination with death began in childhood. One of my earliest memories centers around a green inchworm I found while playing outside, which I was enamored with. It held my five-year-old attention for what seemed like hours but was probably closer to thirty minutes. When it was time for our play date to end, I naturally decided to store this new friend inside our mailbox for later. The inchworm wasn’t too keen on this idea, and while trying to escape, it was promptly bisected as I closed the lid. It's certainly not as traumatic as other people’s brushes with mortality, yet for my young mind, it carried more weight than the deaths of family pets I’d previously experienced. Here, death had occurred right before my eyes. There was a kind of shock that came from the finality of it, so significant that I can still recall the experience 20 years later.

As the years passed, my curiosity about this inevitable end only grew. Although I also came to love horror movies and ghost stories, my interest extended beyond morbid fascination. I remember loitering at the very end of the "bodies” exhibit in the local museum, reading about the process of decomposition. The mechanics of decay, the various methods used for corpse disposal and memorial – these things were relevant to me, and every single person I knew. As much as we avoid talking about it, death is one of the few things every living being has in common. This infatuation with the ways in which it relates to us is what eventually led me to begin exploring cemeteries.

Photo by Danni Matter

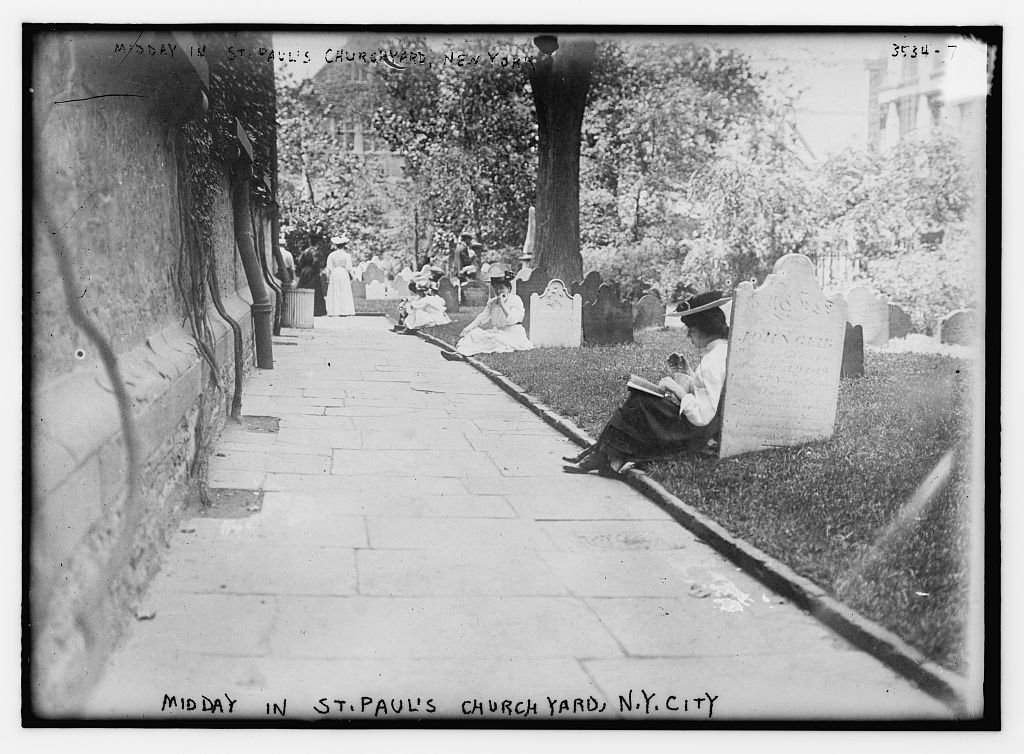

When I pull up for a stroll through the gravestones with my umbrella (necessary when you live in the Sunshine State), I’m not being inventive. During the second half of the 19th century, cholera and yellow fever were killing off Victorians at an unfortunate speed. Death became such a large part of American and British culture during this period simply because there was so much of it happening – illness could take you or your loved ones at any time. A change in cemetery design was also occurring; previously, corpses were put to rest in churchyards or cramped municipal burial grounds. Churchyards were generally inaccessible to the public and were somber places meant for engaging in prayer and repentance. In the 1800s, there were new cemeteries being built outside the crowded city centers, and they were much more welcoming. Rather than being closed off and populated by warnings against sin, they were like gardens: sprawling green landscapes dotted with trees and flowers. This would have been especially intriguing to the residents of many major cities that did not yet have parks or recreational areas.

Picnicking became a popular activity at the time, and many gatherings within these new cemeteries were just that. Victorian ladies with their parasols (the blueprint) and children in tow would lay out a blanket and have lunch with their late husbands, parents, and siblings. These people were coping with constant grief and fear that they might be the next to die, which one might think would cause them to steer clear of memento mori. And yet the opposite was true — they developed a closer relationship with death. They spent time at the graves of people they had loved, talked to them, and shared meals in their honor. Versions of this ritual can be observed globally: Día de los Muertos in Mexico, the Obon Festival in Japan, and Radonitsa in Eastern Europe. During these days of celebration, the living comes together in places built for the dead. But while foreign traditions have persisted, Americans over time have lost their penchant for dining with the deceased. Every cemetery I’ve visited has been mostly or entirely devoid of human life. Why?

Photo from the Library Of Congress

Since the 19th century, our attitude toward death and dying has become increasingly avoidant. One reason is that many Americans no longer care for their deceased loved ones at home, rather entrusting the bodies to a funeral home. Despite being unnecessary in many cases, embalming has spent years being pushed by funeral directors, to the point where it’s now become commonplace. This has further distanced many of us from the realities of physical decay. Some cemeteries have even made a point to eliminate visual aspects that serve as reminders of mortality. In an episode of the podcast Death in the Afternoon, co-host Sarah Chavez discusses the transformation of Forest Lawn in California from a graveyard into an idyllic "memorial park.”

Dr. Hubert Eaton, who managed the property for 60 years and was responsible for its development, wrote, “We pictured life, not death. We carefully eradicated familiar signs. We substituted winged doves, swimming ducks, singing birds, splashing fountains – everything [symbolic] of life. We eradicated even the trees, that lose their leaves in the wintertime, suggesting death.”

Eaton even went so far as to remove the headstones protruding from the earth, replacing them with flat grave markers so as not to obstruct the view. I still see these same kinds of markers used in many modern cemeteries. For decades, the funeral industry has been capitalizing on our innate fear of death, building walls between us and the things which make us human. At this point, “denial of death” has become a part of our culture. Of course, it’s a difficult topic, but by ignoring it, we aren’t able to face our fears and hopefully arrive at a place of acceptance.

In my opinion, returning to the tradition of visiting cemeteries is a great place to start. Although we now have dedicated parks for picnicking and recreation, cemeteries still have their own unique charms.

Photo by John McCoy - Oxnard, CA

For one, there is so much to be learned about local history and traditions! Often, I’ll notice a last name that’s especially prevalent, with generations of members interred. These may be some of the first families to settle in the area; a quick online search can tell you about their role in that area’s development. While exploring the city cemetery in Miami, I spotted a couple of eggplants left among the graves. After some research, I learned that they are left as an offering to Oyá, an Orisha of the Yoruba and Santería religions. The Green-Wood cemetery in New York City, the largest and most breathtaking I’ve set foot in so far, is worth a visit if only to traverse its grounds. In its center, you can find a circle of headstones dating back to the mid-18th century. They’re engraved with traditional Puritan symbols, including winged skulls and hands pointing toward the heavens. Many headstones in Green-Wood also feature a metal stamp reading “perpetual care”, which I haven’t seen anywhere since. The implication is that the family contributed to a specific fund to have the gravesite maintained indefinitely. I never would have discovered all of this and more had I not been there. Even with a world of information at our fingertips, there are some things we’ll never understand without experiencing them firsthand.

Even if you have no friends or relatives interred, most cemeteries are open to the public during certain hours. You are the only one preventing yourself from visiting for the purpose of paying your respects, admiring the aesthetics, and reflecting. When I pitched this article, another Trash Mag contributor posed the question:

“But what do you do there?”

There are many possible answers to this. I was sent a TikTok video recently of someone who prepared food from recipes they found inscribed on headstones. There are organizations working to preserve cemeteries that have fallen into disrepair; many accept volunteers who want to assist in restoring these sites so that future generations will be able to visit and learn from them. For me, simply observing is enough – reading over the engraved names, and imagining what their owners’ lives may have been like. At the risk of sounding macabre, I even enjoy being close to the bodies. I'm reminded that one day I’ll join them, and as the saying goes, we are all equal in death. It elicits a feeling of unity with those who have come before me, and those who will come after.

Photo by Danni Matter

There is such a wealth of knowledge to be gained about the self, and about others, by spending time in the places we put our dead to rest. You don’t need to slam the brakes every time you see a cemetery on the side of the road (like I do) but just consider stopping by. Record interesting things you find and research them. Take time to be quiet and sit with someone.

You may be the first one to visit them in years.

The Evora capela dos ossos (chapel of bones) in Portugal is a stunning work of art constructed by Fransiscan monks using over 5,000 sets of human remains. It has existed since the 1650s, its purpose being to encourage virtue by reminding visitors of their inherent transience. One wall features a plaque, which imparts this message:

“Where are you going in such a hurry, traveler? Stop. Do not proceed any further. You have no greater concern than this one. Recall how many have passed from this world; reflect on your similar end. If by chance you glance at this place, stop. For the sake of your journey, the more that you pause, the more you will progress.”